| Justin Bieber at the Sentul International Convention Center in West Java, Indonesia (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

As simple as this seems, I am fascinated by how quickly it can break down in practice. Announce publicly on the Internet that you have used iOS and Android devices and prefer one to the other, and you will see what I mean. Many people will tell you that you are wrong; some will even condemn you on the basis of which smart phone OS you prefer. You'll see the same thing with sports teams, game consoles, and all sorts of other things. But as long as you are stating your preference and not making claims about how X is objectively better than Y, your preference isn't right or wrong; it just is.

You may love the music of Justin Bieber and look forward to hearing the Christmas music that plays in all the stores every December. I may think you are nuts for doing so, but I can't really argue that you are somehow wrong to do so. You may be equally puzzled by my enjoyment of the music of bands like Cannibal Corpse or Slayer, wondering how anyone could like a band that just sounds like noise to you or that sings about such awful things. We clearly have different preferences, but that would seem like a silly basis for condemnation. At least, it should seem like a silly basis for condemnation, shouldn't it?

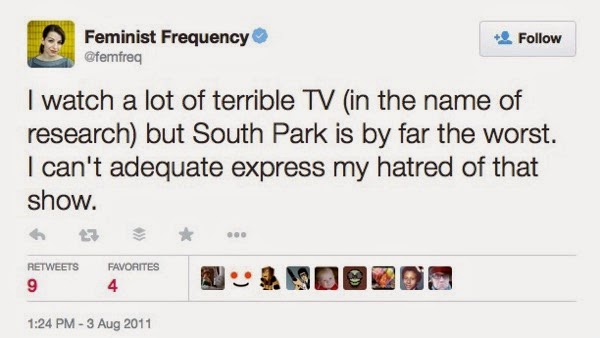

The problem is that some of us (and I think we all make this mistake from time-to-time) forget that our preferences are just preferences and begin to act as if they were facts or even moral imperatives. I've made no secret of the fact that I enjoy South Park. I don't love every episode, but I generally enjoy it and find it funny. I don't go around telling others that they should watch the show, that they should like the show, or that they are wrong if they dislike it. That's none of my business.

Others hate South Park with a passion, going out of their way to condemn it publicly.

And this is perfectly acceptable because it involves someone sharing their preference with others. It does not become problematic until we begin use our preferences as a basis for making value judgments, condemn each other for our preferences (e.g., "If you like South Park, you must be an awful person"), or seek to control someone else's behavior on the basis of our preferences (e.g., #cancelcolbert). As soon as we start to do these things, we are turning our preferences into demands.

What is the difference between a preference and a value judgment? Value judgments involve claims that something is good or bad in a broad sense (e.g., "South Park is horrible show with no redeeming qualities"); preferences are statements about the person making the statement (e.g., "I think South Park is funny"). We can meaningfully argue about value judgments; this is not the case for preferences.

The fact that someone hates a TV show I like, listens to music I can't stand, or prefers to use a different brand of smart phone does not make them a bad person. If they are going around making factual claims about the world or value judgments, they might be wrong; if they are merely expressing a preference, there is no meaningful way in which they can be wrong. To hate someone on the basis of the things they like or dislike places one on shaky ground even if it seems to happen fairly often.