You have a great idea for an invention that is practically guaranteed to be a big moneymaker. Even if it does not live up to the various advertising claims you would make about it, it will sell well and earn you a fortune. In fact, no amount of scientific proof that your invention does not do what you will claim it does is going to hurt your sales. Sounds pretty good, doesn't it? There is just one small problem. You see, you know that your invention does not work. So you couldn't ethically market it as doing something that you knew it couldn't do, right? Not so fast! Things are not quite as simple as I've made them sound. Your customers are absolutely convinced that the device works, and no amount of evidence to the contrary is going to dissuade them.

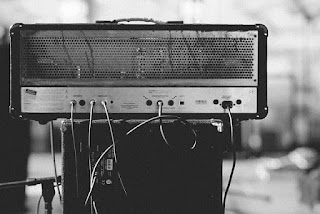

I want you to imagine that the invention I described above is a prayer amplifier. And now we'll consider the ethical implications of selling such a product.

At first glance, it would be morally wrong for me to sell a prayer amplifier. It does not work, and I know it does not work. Selling it anyway would be dishonest and exploitative. But what is it about my selling such a product that bothers us the most - that the device does not work or that I know that the device does not work?

If we are mostly bothered by the fact that the device does not work, regardless of what I think about the device, then we are dealing with a "truth in advertising" issue. We are saying that it is morally wrong to sell a product that objectively does not perform the claimed function regardless of what those selling it believe about the product. By this line of argument, we would have to conclude that the entire nutritional supplement and vitamin industry is morally wrong. Are we prepared to make such a concession? If so, what other industries would we eliminate?

Suppose instead that what bothers us about this scenario centers on my knowledge that the device does not perform as advertised. Would it make sense to grant me a reprieve if I actually believed in the defective product? If I was convinced that it worked even if the evidence said that it did not, would this absolve me of my responsibility for selling the product? That seems like an odd argument to make, doesn't it?

Here's the thing, whether the prayer amplifier works or whether I think it works are both irrelevant. What really matters is whether prayer works. I think that the moral queasiness most of you are feeling at this point has nothing to do with the prayer amplifier and everything to do with me trying to make a buck off of prayer, something we all know does not work (using the standards we typically apply).

Suppose I build a prayer amplifier which I claim "helps (my preferred) god hear your prayers." Further, suppose that I run infomercials on cable in which I explain that the love of my "god" cannot be scientifically measured and that those trying to discredit my device are merely jealous. We all know I'm full of shit, and I think that this is what bothers us far more than what my device does or whether I am deluding myself. Would this mean that we would regard the entire industry of Christian merchandise to be morally wrong?

Do the millions of devoted Christians who will buy my device not bear some responsibility here? After all, who can say for sure that none may be helped by using it? The placebo effect is a powerful thing, and if it makes them feel better...

Here is the question for you to consider: If you believe that it is morally wrong for someone to sell a prayer amplifier, what exactly makes it wrong?

An early version of this post first appeared on Atheist Revolution in 2009. It was revised and expanded in 2020.