There is a scene in The Waterboy

Professor: Now, last week we talked about the physiology of the animal brain as it pertains to aggression. Now, is there anyone here that can tell me why most alligators are abnormally aggressive? Anybody? Anyone? Yes, sir. You, sir.

Bobby: Mama says that alligators are ornery 'cause they got all them teeth but no toothbrush.What happens next? The class laughs at Bobby, and the professor delivers a gentle mocking. Bobby looks around the room, almost as if he is surprised by the reaction of his classmates. He tries to answer another question with similarly poor information and is again greeted with laughter and ridicule. And eventually, Bobby appears to learn not only that there is a social consequence for providing blatantly incorrect information in class but that his information may in fact be incorrect. He begins to learn.

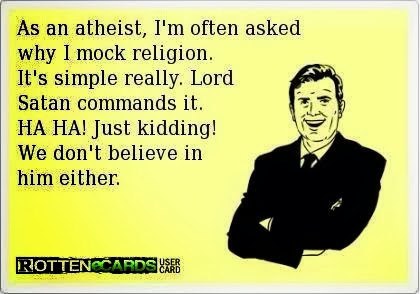

The question of how we atheists should respond to religious believers when they spew religious nonsense has been hotly debated for far longer than I've been around. Should ridicule and mockery ever play any part in how we respond to religious believers? Some say yes, and others say no. Those who say no are correct to point out that ridicule can lead some believers to cling to their ridiculed beliefs even more intensely. They are also correct to point out that ridicule and mockery can lead others to form negative opinions of those using these methods. In fact, those who say that ridicule and mockery should not be part of our response make many good points. And yet, I do believe that ridicule and mockery belong in the atheist's repertoire. While they should not be all we do, I think they can be part of what we do (i.e., tools with a purpose).

Ridicule and mockery are not always effective, but they can be effective. Whether it is pleasant or not (usually not), the experience of being mocked or ridiculed can provide someone with the opportunity to learn from their mistakes. I have personally changed my mind on many issues, including some deeply held beliefs, as a result of a process of research and self-examination set in motion by ridicule. I am not talking here about trivial bits of factual knowledge but about complex subjects like sexism, gun control, abortion, and the like. I have to assume others have had the experience of being motivated to learn through mockery and ridicule.

Suppose Bobby had been homeschooled by evangelical fundamentalist Christian parents until college. Is it unrealistic to imagine that he might take a science course and have his creationist beliefs challenged for the first time? And if not, is it unrealistic to imagine that this experience, even if it included some mockery and ridicule, might not produce learning? At the very least, he might learn that saying certain things in public will lead to ridicule by his peers. That might seem like a cruel lesson, but I'd argue that it could still be valuable.

And are there not scenarios where creative mockery and ridicule might be among the best options we have available to us? In the U.S., a Christian extremist has the right to stand on a street corner holding a sign with an absurd message. Why not pick up our own sign and take a place next to him? This probably won't change his mind, but it may dilute the impact of his message.

As I have written previously, one of the things some critics of mockery and ridicule occasionally miss is that these particular tools are not always aimed at changing the target's belief system. Sometimes, they are aimed at reducing the influence of public religious beliefs. Other times, they are done more for the benefit of the audience rather than the target. The distinction between private beliefs and public beliefs is an important one, and mockery and ridicule are most often aimed at countering dangerous beliefs made public.

In a previous post, I wrote:

Like it or not, humans are social creatures who can and do learn from social pressures. When someone says something stupid and is greeted with resounding laughter, temporarily becoming the butt of their friends' jokes, they tend to refrain from expressing the same sort of stupidity in the future.Admittedly, this is different from changing someone's mind. And yet, it might be almost as good in some circumstances.